AMGA Partner Athlete Profile: Kel Rossiter with Mammut

The AMGA is excited to announce our blog series, running through 2015, featuring Q & As with AMGA guides, instructors, and members who are integral members of our corporate sponsors’ athlete teams—men and women who are delivering both in the guiding world and as ambassadors for their brands and chosen outdoor sport(s). There is and always has been much overlap between mountain guides and top mountain athletes: guiding and teaching are a natural fit for those who excel in skiing, rock climbing, ice climbing, and mountaineering, as the activities pull from the same passion, wisdom, and skill set.

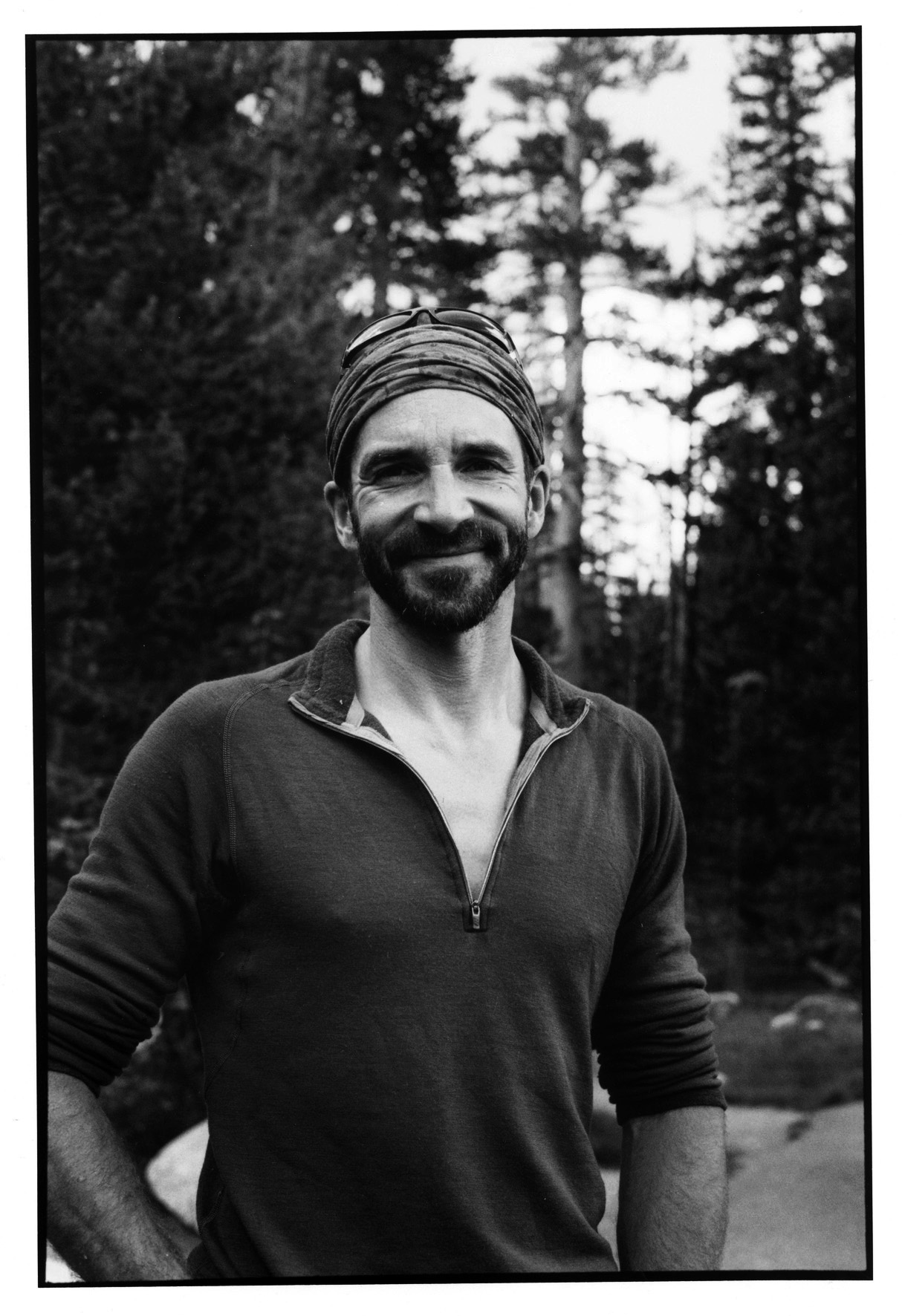

This week’s mini-profile is of AMGA Rock & Alpine Guide Kel Rossiter, an athlete for our partner Mammut.

Kel Rossiter, List of AMGA Certifications

- AMGA Alpine Guide

- AMGA Rock Guide

- AMGA Ski Guide Aspirant

- AMGA SPI Provider-in-Training

How did you get into climbing, and then guiding?

As far as climbing in the bigger ranges goes, I was part of the Cotton Council of America’s first ascent of Washington’s Mount Adams. Realizing that this sponsorship was ultimately doomed, I decided to get some training and enrolled in a community-college mountaineering program based out of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. With that as my entry into the mountains, I decided to pursue outdoor leadership professionally in the realm of collegiate programming. After getting a master’s degree in outdoor education, I became the director of outdoor education at Georgetown University. I loved the students and all they taught me. Over time, I decided I wanted to learn more about learning, and got a doctoral degree in educational leadership. That experience helped me to see that I wanted to work with people at all ages and stages in life, blending both outdoor leadership and instruction, so I set about creating my own guide operation.

Why do you love guiding?

“Guiding” means different things to different people. And it also means different things depending on what country or continent you’re in. Fortunately for me, in America “guiding” tends to often blend both leadership in the mountains and instruction about how to safely and efficiently travel in the mountains independent of a guide. I particularly enjoy working with climbers who are building their skills so as to tackle a progression of objectives, both on their own and with a guide. One time I was visiting Eustace Conway (the frontier-skills fellow who was the subject of a popular book called Last American Man) and he related to me his take on a classic story—it opened up my perspective on what it means to be a teacher. In his North Carolinian drawl, he told me:

Ya’ know, there’s that old story that if you give a person a fish, he’ll eat for a day…and that’s niiiice. And they say if you teach a person to fish, he’ll eat for a lifetime…and that’s purty good. But I think that if you can teach a person how to learn, well, he won’t have to eat fish all his life.

I hope that through bringing people into challenging and stimulating environments and providing a safe space for exploration, I can help them learn how to have their own adventures and ultimately, perhaps, how to learn..

Why is standardized guide education important, especially now?

I’m both vehemently against standardization and a radical proponent of it. There are two sides to the standardization coin, depending on how you approach the idea of standardization. On the one hand, standardization of techniques, practices, and protocols is a vital part of the developing guide profession in the United States. As with any profession, the body of experience can lead us toward a more effective set of practices. On the other hand, the idea of “standardization” can lead to a moribund, regimented, and lifeless way of being.

I don’t think anyone who goes into the guiding profession seeks to live a standard life—and fortunately the AMGA training process mirrors this pursuit for something beyond the standard: Guides learn that the standard is to push the standard forward. As the inimitable Marc Chauvin said to me toward the close of my Rock Instructor Course, “Remember…if you’re doing the same thing that I’ve taught you five years from now—you’re doing it wrong.”

What is in your pack on a typical day of guiding?

I guide summer alpine on Rainier, in the North Cascades, and sometimes in Alaska. In the autumn and spring I’m guiding rock in the Northeast. In winters, it’s Northeastern ice. I love that there is no typical day of guiding. It asks me to consciously consider each day that lies ahead. Regardless of the day, there’s always a first-aid kit and a headlamp: plan for the best, prepare for the worst. Beyond the particular day, environment, and activity, I try to keep in mind the words of adventurer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who said that, “Perfection is achieved not when there’s nothing more to add, but when there’s nothing more to take away.”

Trimming it down to essentials involves paying attention. When you roll into camp at the end of the day, do you always have extra water? When you roll back to the trailhead at the end of a trip, do you always have extra food? Sure it’s good to have a margin for the unplanned error, but if your margin is wide and consistent, then you’ve obviously packed to much.

My Mammut Masao hardshell is a frequent addition on “iffy” days regardless of season—light to pack and watertight. Beyond that, I focus on the specific activity and, hence, applications. For steep ice, Nomics are always strapped to my pack and BD Stingers are packed inside. If it’s rock, you’ll find a set of Miuras in my pack. Going into the alpine, a high-fill-rating parka like the Eigerjoch is indispensable, and since it’s always nice to roll into camp with warm and dry feet, a spare pair of Darn Tough Pinnacle socks is in the pack to replace the ones on my feet.

Beyond the equipment, there is the fuel. I like to bring a blend of performance foods and “everyday” foods, so I’ll typically have a few Honey Stinger Energy Chews and Gels, combined with some kind of sandwich, burrito, or even those tikki masala packets from Trader Joe’s. Feed the machine!

What has been your best day out guiding, and why?

There’s a climber whom I’ve been guiding and instructing in the Northeast for the past several years. He’s been building his skills in a steady and methodical manner, and last season he’d gotten confident in his WI3 leads and is super-solid following WI4/5. We had a fantastic day at Lake Willoughby, swapping leads and getting up some impressive lines. At the end of the day, he commented on just what I was thinking, saying, “You know, it’s all finally coming together—we started off with you belaying me up some toproped pitches and now…look at this!” That fellow had learned how to fish—and I think somewhere in the process he’d also learned a bit more about how to learn.

What has been your worst/funniest/most comedy-of-errors day out guiding, and why?

Though it wasn’t exactly guiding, it happened when I was directing a collegiate outdoor program— it was probably the strangest moment in outdoor leadership I’ve ever had. I was with a group of student-leaders-in-training. It was late October. We’d arrived in Shenandoah National Park—a very thin stretch of land along the Skyline Drive—and hiked in a mile or so in the dark to set up camp. As we were setting up camp, my student assistant came over to me and said she’d heard something weird in the woods. I assured her it was a deer. But when she came back again, I went over to investigate.

She was right—it clearly wasn’t a deer. Far off in the darkness, someone was running from tree to tree and making weirdly human, but unearthly, cackles. They sounded insane. Grasping for an explanation, I thought maybe there was some kind of sanatorium near the border of the park and someone had escaped. The students were all clearly freaked, crowding around me. So I settled on a strategy of appeasement, talking to the apparition and telling him essentially, “We’re sorry we’ve come into your space and just give us a few minutes and we’ll leave.”

It didn’t seem to work. And, as he ran from tree to tree howling and getting ever closer to our group, a student stepped up to me, said, “Here, you might need this,” and put a six-inch blade in my hand. Seeing that my appeasement strategy wasn’t working, I decided to give the authority-approach a try, shouting to him, “You need to get out of here right now!” That didn’t work either and he was now less than thirty feet away, darting from tree to tree, and getting closer. It was dark, but he seemed to have a weird face. Finally, he was at the last tree between us and he started sprinting toward me. The students screamed. I clutched the knife, wondering what I might do with it. Then, less than fifteen feet in front of me, he pulled off what was a mask and hollered, “Happy Halloween!”—showing himself to be Luke, one of our students.

Needless to say, Luke and I had a talk after that incident, and though I was one thin hair away from kicking him out of the program, I didn’t, and the happy outcome is that he went on to become a stellar student leader and a friend. And, since even the weirdest incidents offer us some lessons to learn, I’d say this: In all future emergencies involving a crazy guy roaming around in the woods, I’ll always conduct a quick head count to see if maybe one of my own is the crazy guy.

What is the one, most essential trick you’ve learned to make you a more efficient guide or climber?

I learned a phrase while in the Army, but it didn’t really make sense to me until I was a guide: “Move with a sense of purpose.” I love that idea of purpose: Not hasty, so as to lose grip and make mistakes, but not so out of your brain that you’re moving at a snail’s pace. Seriously, it’s easy to look at climbers taking off their crampons and quickly determine whether they are actually taking off their crampons or if they’re thinking about what they want to order back at the bar and grill, while fumbling with their crampons. Focus on what’s in front of you and do it with purpose.

What is the one item you can’t live without?

My brain. I try to take it with me everywhere, so that I can develop workarounds for anything I don’t have.

How do you let loose/relax when you’re not working?

Hanging out with fellow guides is a great way to either let loose or relax—such a varied and talented bunch: I always come away with new ways of looking at my work or the the world. This often occurs while climbing. Sharing time with my wife is also big—she’s an avid climber and outdoorsperson, but she’s not overly hydrated with the climbing or guiding punch. She continually helps me to see that there is a huge reality beyond carabiners and climbing ropes—arts, culture, community, cuisine, and the like. I’ve also been exploring a bit of wildlands foraging—it’s my substitute for gardening, since my guide schedule doesn’t allow that. Beyond that, I’m a fan of meditation: Guiding involves so much yin-action, I find it helpful to throw in the yang.

What are the top three songs on your playlist?

I love the seasonality of guiding, and I find that my playlist changes with those seasons. Three, really?!?–I feel like I’m being asked to choose my favorite cam size—it’s a matter of situation and application! Here’s 10 from late summer:

- Courtney Barnett: Depreston

- The Radio Dept: Death to Fascism

- Vampire Weekend: Unbelievers

- Grimes: Genesis

- Aer: Floats My Boat

- Mötley Crüe: Wild Side

- Metric: Wanderlust

- Public Enemy: He Got Game

- Johnny Cash: Devil’s Right Hand

- Metallica: Master of Puppets