ELECTRONIC NOISE AND WHAT IT MEANS FOR YOUR BEACON

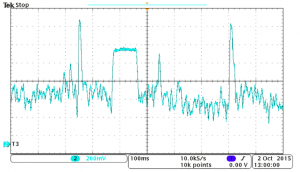

Oscilloscope visualization of “random noise” being picked up by a transceiver. The flat-topped signal is from a transmitting beacon, the pointed spikes are from a source of active interference.

If you don’t recognize the phrase “electronic noise,” it’s time to get acquainted. This two-word phrase has a big impact on the performance and accuracy of your avalanche transceiver, the one piece of equipment that absolutely cannot go bad when you or your backcountry partner gets buried.

The rule of thumb that BCA promotes is to keep any possible sources of interference, passive or active, 20cm (about 8in) away from your beacon when it’s in transmit mode and 50cm (about arm’s length) when in search mode. This is particularly important when searching, as interference could impact your beacon’s ability to determine the correct distance and direction of your target. When searching, holding your beacon at arm’s length is a good technique to practice and follow so you can keep your eyes on the bigger picture and make larger brackets during your fine search.

BCA Athlete Tatum Monod illustrates beacon searching. Always keep your transceiver at arm’s length when performing a search, not only is this good technique, but it will ensure no interference from electronics on your body.

HOW IT WORKS

When in transmit mode, every beacon sends out an electromagnetic pulse (emitting at 457kHz). A beacon in search mode receives this pulse and interprets it using built-in antennae. Your digital transceiver takes the information and analyzes the pulse to help you determine distance and direction to the target.

In addition to the target beacon’s transmission, the searching beacon will also pick any radio frequency noise that happens at same frequency, as well as harmonics of this frequency. These garbage pulses are what we call “electronic noise” and could be picked up, even though this additional noise is just “junk” and not, in fact, the beacon you’re looking for. Anything in the 457kHz frequency is interpreted as a possible target beacon, and when the noise gets “loud” enough, interference causes false signals in the form of false or erratic readings on your beacon’s display. If there’s enough background noise, then the “noise floor” can be high enough so your transceiver has a hard time picking the signal out of the noise. This causes a decrease in reduced range or erratic readings on your beacons display.

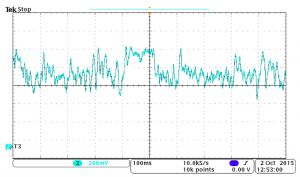

This shot from our oscilloscope shows a high noise floor, making it difficult for the transceiver to make out the transmit pulse in the center of the screen.

A good analogy is to think of trying to strike up a conversation in a bar. Early in the night before the crowd trickles in, there will be background noise, but you’ll still be able to hear the person sitting across the table from you. Later on with the DJ playing and conversation volume rising a few decibels, you definitely won’t be able to hear the person across the table, and you might not be able to hear the person standing right next to you.

While you probably know the most common sources of interference and electronic noise, some of the less common culprits may surprise you. To learn more, it’s best to start with the two basic. categories of interference: active and passive.

ACTIVE INTERFERENCE

Active interference is caused by electronics that actively transmit frequencies. Pretty much everything with a battery is a potential source of noise. The most common and well-known culprit is probably in your pocket right now: your cell phone.

Your cell, particularly if it’s a smartphone, gives off a significant amount of competing noise when it’s on and the screen is illuminated. If you think that setting your phone to airplane mode is enough to cut noise, think again. Airplane mode does not significantly alter the amount of electronic noise the phone gives off. Hold a phone set to airplane mode too close to a searching beacon, and your numbers will be affected as much as if the phone were fully “on.”

Active interference is caused by electronics that emit radio frequency noise intentionally or unintentionally. Sources include GPS devices, iPods, radios, point-and-shoot cameras, video cameras (like GoPros), snowmobiles, snowbikes, the keyless entry fob on your keychain, and, believe it or not, headlamps. A good rule of thumb to follow is to assume that anything you are carrying that is powered by electricity i is potential source of radio frequency noise.

Headlamps are a particularly interesting example because they beautifully visualize the movement (and potential dangers) of competing frequencies. Set to high, the LEDs in a headlamp emit a strong, constant stream of light. Set to low or medium, however, the headlamp doesn’t turn off LEDs to create a dimmer glow. Instead, the LEDs pulse. The pulse is so fast that the human eye doesn’t register a “flickering” phenomenon. Instead, your eye interprets the pulse as less light and a dimmer beam. The photo above was taken at night with a long exposure, showing the individual pulses from the LED.

Have to perform a search at night? Set your headlamp to high. The full-force, steady beam causes less interference than other settings. Otherwise, turn it off.

Snowmobile spark plugs cause a lot of interference issues, so be sure to park your sled a safe distance away from your search area.

PASSIVE INTERFERENCE

Passive interference comes from sources that partially block or warp transmissions. Passive sources are usually only a problem if they are very close to your beacon, and impact transmissions by affecting antenna performance, usually by slightly weakening the signal or slightly altering the shape of the electromagnetic field, which could cause minor “spikes” or “hiccups” in distance or direction readings. While under normal circumstances passive interference should not be enough to significantly interfere with or ruin a search, BCA does recommend that users stow sources of passive interference (usually metal) 20cm away from the beacon when in transmit mode. This recommendation is made to prevent a situation where a transmitting beacon gets shoved into or against metal during an avalanche.

Metal is the primary problem source in this category, but magnets can also cause problems and should be treated with care. Sources of metal are varied, from the obvious (like your avalanche shovel blade), to the small (your pocket knife), to the surprising (did you know Gu packets are lined with metal?). Aluminum foil, like the thin layer that insulates a Gu packet or the wrapping of your homemade PB&J should be kept well away from beacons, whether that means in a separate pocket or in your pack. Also, be aware of some jackets that use magnets instead of zippers, as these have been known to change modes on some transceivers.

ENVIRONMENTAL INTERFERENCE

Complicating matters is the fact that you will not be able to control and eliminate all potential sources of interference. A number of natural and man-made circumstances and features can increase the level of electronic noise and negatively impact your transceiver’s ability to accurately pinpoint its target.

These uncontrollable sources include thunderstorms, which increase the level of electricity in the air even before any lightning strikes. Overhead power lines, cell and radio towers, and underground power lines for chairlifts can also cause real problems when searching.

All sources of interference, from cameras to power lines, have ambient electronic signals that may reduce search range and slow your beacon processor’s ability to update reliably as you’re moving through your search pattern. This produces readings that are not as accurate as they might otherwise be and can confuse the search party. In those cases when you cannot remove all major sources of electronic noise, the International Commission of Alpine Rescue (ICAR) recommends altering your signal search pattern (the first phase of the search when you don’t yet have a signal) to 30 meters rather than 40 meters, for greater accuracy.

BEST PRACTICES

There is a lot of variation in how much interference a given object gives off. Two identical iPhones, for example, can give off different levels of electronic noise. A certain level of variation comes from minute inconsistencies in the manufacturing process. Even more variation develops as you use and abuse your electronics. Wear, tear, cracks, and water damage all have the potential to increase interference. Which means, unfortunately, that guidelines are never one-size-fits-all.

The best way to mitigate the risk of interference is to follow the rule of “better safe than sorry.” A few key tactics:

- Turn unneeded electronics completely off at the start of your tour and stow them in your pack.

- Any electronics that you don’t want to turn off should be stowed in a pocket or pack at least 20cm away from your beacon.

- Want to stop and take a photo? Take out your phone, snap the picture, then return it to its carrying place at least 20cm away from your beacon.

- Keep all sources of metal, from shovel blades to food wrappers, at least 20cm away from your beacon.

- When it’s time to search, hold your beacon at arm’s length (50cm) to limit interference and keep your eyes on the big picture.

- Park your snowmobiles or snowbikes (and anything else with a spark plug) well away from the search zone.

- If you suspect unavoidable interference is negatively impacting your beacon readings, reduce your search strip widths to 30 meters when performing a signal search.