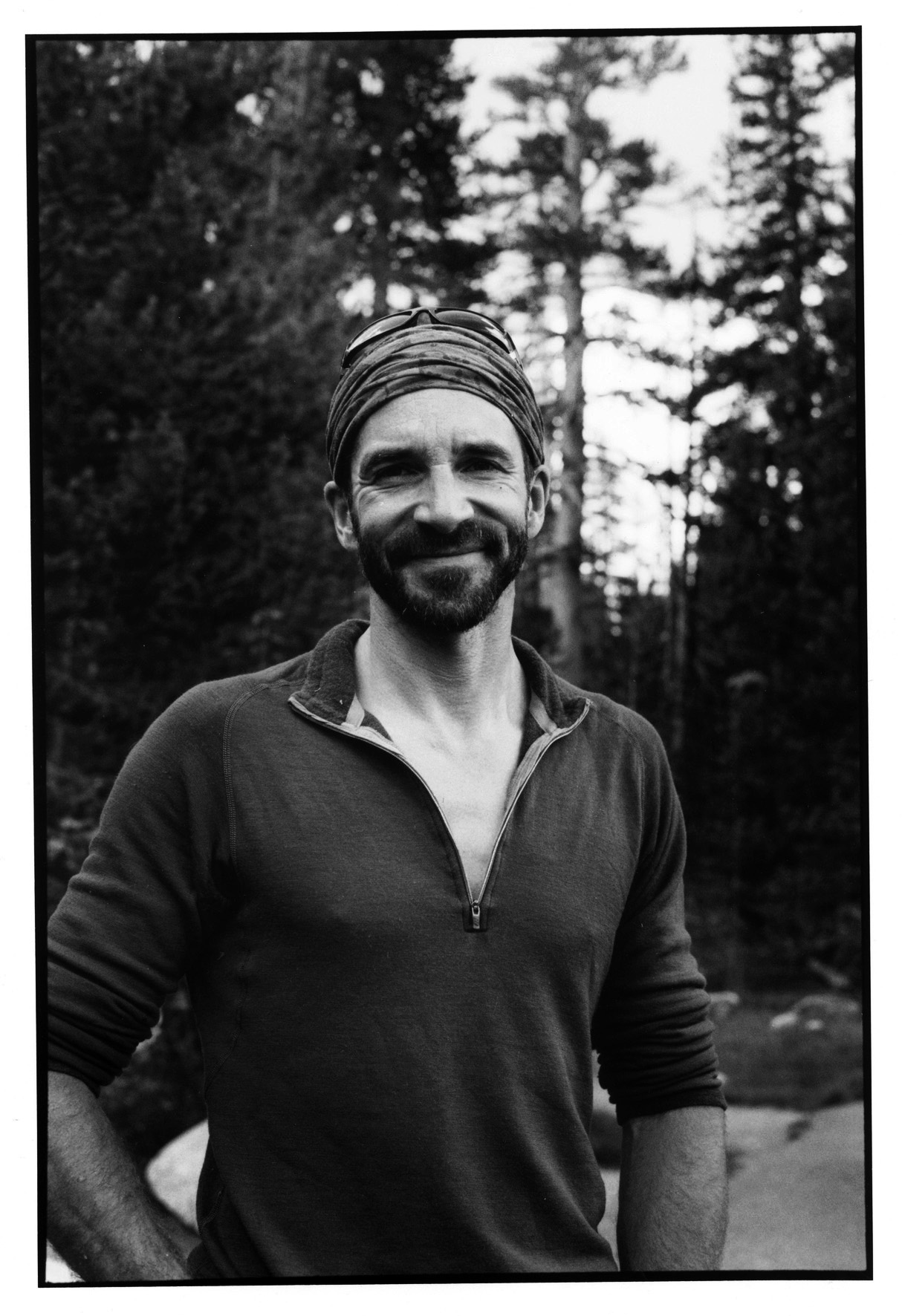

Micah Lewkowitz, Recipient of the 2015 Walker Family Foundation Scholarship

professionalism

prəәˈfeSHəәnlˌizəәm/ (noun)

the competence or skill, good judgment, and polite behavior expected of an expert in their field.

I started guiding in 2006 for a small company based in Western Massachusetts, mostly toproping and backpacking trips along the Appalachian Trail. By 2008, I began guiding in the glaciated mountains outside Haines, Alaska. I remember, every time while in these mountains with clients, thinking how amazingly lucky I was to work in such a beautiful, dynamic, and challenging environment. At this early point in my career, I had been avidly climbing for six years, but still lacked the professional education to guide these remote mountaineering and alpine objectives as safe and efficiently as my senior colleagues. I was missing the critical middle step of mentorship and training, and though it was a slow process for me, I realized that I needed this guidance and support network of a professional mountain guiding organization. We all learn differently, but I’m certain that Thomas Edison wasn’t guiding big mountains when he said, “I have not failed, I’ve just found 1,000 ways that won’t work.”

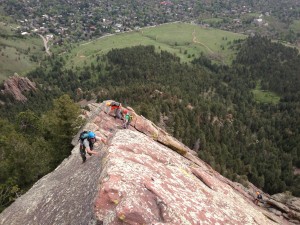

The American Mountain Guides Association offers training and rigorous examinations to ensure that the guides operating in America’s mountains meet the highest level of technical expertise. Generally this course spends the first few days covering the intricacies of shortroping at the rocky crags along the Front Range. After a day of snow school, covering movement skills, snow anchors, and crevasse rescue, the remainder of the course focuses on student-led guiding objectives in the alpine environment. Classics in the area include the moderate snice and rock steps of Dreamweaver on Mt. Meeker, the exposed Blitzen Ridge on Ypsilon Mountain, and the easily accessible Ptarmigan Fingers on Flattop Mountain, among many others.

As it turned out, this May was one of the wettest in Colorado’s history. With a weak snowpack in the mountains, mud-caked sticky rubber approach shoes, and dripping-wet rock all along the Front Range, our options were severely limited. These challenges could have resulted in a flopped course, sitting around twiddling our thumbs. However, the instructors were tactful, honest, and very devoted to meeting our goals. The best example stands out after turning around at 5 a.m. from the Bear Lake Trailhead in cold, wet, and windy conditions halfway through the course, when we relocated for a second dose of caffeine at the Starbucks in Estes Park. The instructors were genuinely interested in how we might best recover from the morning and encouraged each of us to voice our opinions. We decided to return to Eldorado Canyon for a shortroping and technical-descents challenge course. As that day neared its end, students learned they could operate efficiently on autopilot with only a few hours sleep. We honed our transitions and discovered how effective continuously positive and realistic guides (such as our instructors) can turn a seemingly ruined day into the most successful learning experience of the course for most of the students.

This dedication to providing genuine instruction and building a mountain guiding community in the United States is what makes the AMGA such a powerful organization, one I’m proud to be a part of. It’s clear that each instructor is passionate about ensuring that guides meet the industry standards and is able to operate safely in such demanding environments. I’m grateful to the AMGA and the Walker Family Foundation for this opportunity to continue my career development and eventually become a certified Rock and Alpine Guide.